Your cart is currently empty!

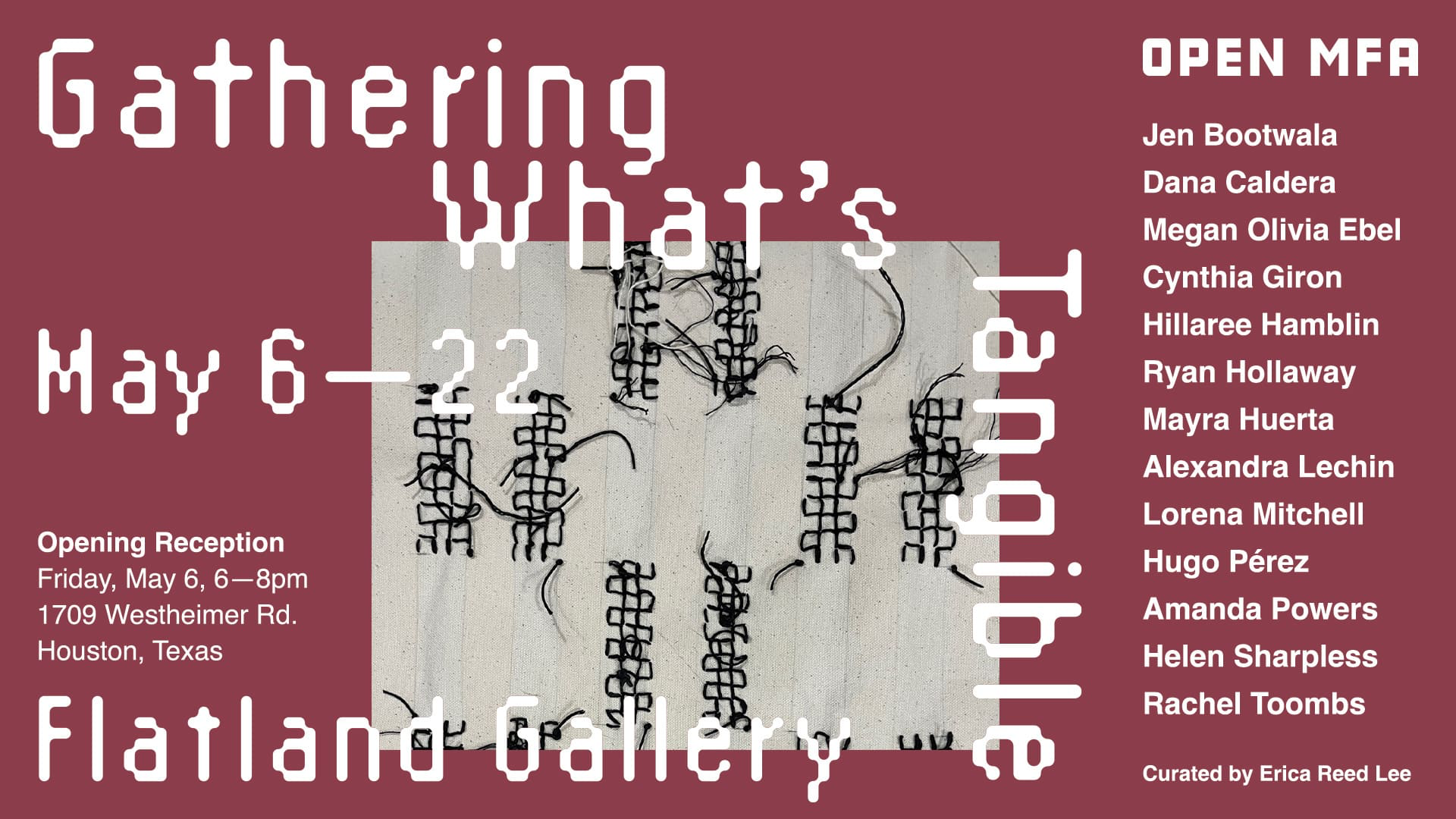

Gathering What’s Tangible Group Exhibition

In May 2020, my collage quilts were exhibited as part of Open MFA’s Group Exhibition, Gathering What’s Tangible. In the curatorial statement by Erica Reed Lee, she describes a trend she saw with artists turning to craft practices during the isolation of the pandemic. I can personally see this in my own work, and in the work of several of my artist friends. Perhaps we craved something tactile, or maybe it was the challenge of learning a new skill.

Exhibition Description from the Open MFA Website

Gathering What’s Tangible brings together Open MFA’s collective response to the pandemic in the form of craft. In March 2020, the pandemic caused Open MFA’s meetings to come to an abrupt stop. Zoom and virtual meetings were a poor substitute for the participatory and energetic events held prior to the pandemic. By fall 2020, Open MFA artists had quietly dispersed. During this time of isolation and anxiety, artists turned towards materiality–many incorporating craft for the first time–as a means of connection and comfort. Open MFA’s inaugural exhibition draws connections between these works and rekindles a community founded on tactile and playful discourse. This exhibition is curated by Open MFA artist Erica Reed Lee.

Curatorial Statement by Erica Reed Lee

Gathering What’s Tangible opened earlier this month at Flatland Gallery in Houston, Texas. I am incredibly excited about this group show, because it is my first exhibition as curator. Swimming in new waters, I was excited and nervous but kept it together.

The origin of the exhibition, like many things, took place in 2020. Open MFA, a collective led by artists Hillaree Hamblin, Ryan Hollaway, Amanda Powers and myself, had originally booked the venue, Flatland Gallery, for another exhibition called “Collaborations”. The exhibition sought to bring artists together across disciplines to collaborate on new work. I pitched the idea to Dan, owner of Flatland, and we scheduled the opening for June 2020.

With the emergence of the pandemic, we postponed the opening indefinitely. Occasionally life would feel safe, but then a surge of cases would hit. We didn’t host another meet-up until January 2022, and it was only then, nearly two years later, did we start up conversations again about a group exhibition.

At our meetings, I noticed that many of us had experimented with craft and new techniques over the course of the pandemic. Amanda started crocheting plastic bags, and I began making artists’ books. Looking at Flatland Gallery, a Montrose bungalow, I thought about positioning the exhibition as a familial coming together–an opportunity to reconnect, share stories of creative resilience, and establish a strong, nurturing foundation for the collective going forward.

By March, I was still consumed by this concept and proposed that I curate the show. The other Open MFA organizers agreed and offered their support (thank you!).

From there, I reached out to artists and made inquiries about the work they had been making since 2020. In some cases, I made studio visits and met with artists one-on-one to select (and sometimes create!) work for the exhibition. This was the most exciting part of the curatorial process. I enjoyed seeing artists’ studios, discovering work in their archives, and listening to their stories. (Thank you to the artists who opened up their studios to me–it is perhaps one of the most generous gifts to share.)

The writing for the exhibition began in March and evolved as the work came together. My thought process also expanded as I read Craft (Whitechapel: Documents of Contemporary Art) by Tanya Harrod and Thinking Through Craft by Glenn Adamson (Thank you, Hirsch Library!). Only when all of the work was dropped off at the venue did I have a formal curatorial statement. Organizing and installing the work was also more organic than I expected. As the work arrived, I adjusted, fielded responses, and made decisions on the spot. Going forward, I hope to have more experience so that I am not doing this the day before…

Weaving, building, sewing, drawing, and mixing, artists found comfort and meaning in the process of learning and making tactile objects.

Entering the exhibition from the from the front door, visitors will see three textile cherubs directly across the room, a bookcase to the left, and a small wooden table with a large mass of knitted sweaters and two knitted calendars on the wall to the right.

In total, there are 30 sweaters in the pile. Jen Bootwala began making them in April 2020. Each one is distinct–a different pattern, a different set of colors. Bootwala found comfort and connection in the process of knitting. Working with yarn offers human touch, warmth, and purpose. The pile, however, reflects a period of confinement and anxiety. The knitted calendars hanging above the pile mark time and Bootwala’s feverish production. Normally Bootwala would have given sweaters such as these to loved ones, but the pandemic restricted this custom.

Time, like yarn’s presence in the exhibition is a direct result of having made a studio visit with the artist. Before our visit together, I was familiar with Bootwala’s thesis work, having seen it in the UH MFA Thesis Exhibition, but I didn’t know any more about Bootwala’s practice or her experience during the pandemic. After we talked about the knitted works in the show and their commentary on graphic design, we talked about knitting more generally. She explained how she started making sweaters and challenging herself with more intricate patterns during the pandemic. We looked at different ways of presenting them in an exhibition. We also talked about a creating a new sweater: one that could not be worn or one that linked people together. Things were left undecided as Jen chose to think about it. A few days later, Bootwala presented the idea of the calendars and began knitting.

The book shelves host Open Library, a collection of artists’ books made by the Open MFA community. In April 2022, I hosted three artists’ books events with Open MFA. At these events, I introduced the medium and encouraged artists to think about their experiences of home and community during the past two years. We then began making books–either collaboratively or independently. Intimate and narrative in nature, these books, brought together, create a collective history and reflect the community’s perseverance, spontaneity, and willingness to find joy. In contrast to the digitally mediated platforms we have come to depend on, this collection is a physical and tangible connection to shared and personal memory.

Next to the bookshelves are three works by Dana Caldera. Books lay open and exposed–their pages torn from their spines. I placed these works next to the bookshelves to juxtapose creation and erasure/destruction of narratives.

Hanging from the ceiling is a large graphic textile titled Separately Together. Six scraps of canvas are sewn together to create a “0” shaped flag. It is a bold yet meticulous collaboration. Positioned off the wall, the flag creates a dramatic shadow.

Separately Together is the only work that began prior to the pandemic. Alexandra Isabel Lechin and I began working on this piece in late February 2020 in preparation for the Collaborations exhibition. The graphic and visual effects were inspired by Lechin’s practice while the concept derived from my interests. I wanted to understand Texas’s history and the various states that had governed and excluded communities within its domain. Can we mend together its complex, murky histories to create a flag?

The exhibition returns from expansive to personal narrative with Rachel Toombs’s Bread Crumbs: On the Path Home. A young girl, somewhat timid, stands surrounded by an antique frame centered in the middle of an array of mixed media pieces. A slew of fabric, layered materials, and color circle outside the frame. Bread Crumbs presents the artist’s journey back to herself. Collage became Toombs’s primary practice early in the pandemic. Cutting and layering, Toombs pieced together a personal narrative with play and spontaneity.

Turning towards the wall opposite of the front door, the viewer finds The Lonely Cherubs: Apathy, Boredom and Relief above a box of curiosities by Mayra Huerta. Lorena Mitchell’s punch needling was perhaps the most surprising discovery during the curatorial process. An illustrator, Mitchell had previously only shown digital works at our Open MFA events. Like many other artists, however, she began playing with craft during the pandemic. The three cherubs depict the range of emotional responses to the pandemic: apathy, boredom, and relief.

Mayra Huerta’s Curiosities I sits below the cherubs on a pedestal. The box of curiosities contains 12 unique objects made of latex, acrylic, twine, and clay. They are peculiar, surprising and bodily. They could fit in the palm of your hand. Beside the box of curiosities, a typewritten sheet describes the unique stories of each object.

Curiosities I demonstrates Huerta’s recent use of both writing and ceramics. Huerta began writing regularly during the pandemic’s shutdown after creating a writing group with her friends. Creating and sharing short stories with one another, Huerta and her friends used writing as a way to connect with one another. Later, Huerta also began ceramic classes and started playing with that medium as well. While Huerta’s watercolors are also concerned with the flesh, Curiosities I offer a more intimate, tactile, and narrative experience. They feel precious and peculiar–much like our selves.

The final piece in the entry room is a small framed piece by Cynthia Giron. The word “libre” (freedom) is flipped backward, and a butterfly flies upward (or is it falling down? It isn’t clear). The Butterfly Effect offers a colorful, coy prelude to the preceding works.

In the following room, Hillaree Hamblin’s microscopic ink drawings expand outwards on the middle wall. Intricate and detailed, these line and dot drawings reflect the manic, yet beautiful, anxiety resulting from isolation and uncertainty. Like a cloud, they suspend themselves.

Dana Caldera’s quilt series hangs across the main room’s eastern wall. This newer series of collage work is a continuation of her previous series with the significant addition of the found quilt pieces’ pillowy, cushioned surfaces. Caldera pulls from the remnants left by strangers to create soft yet rough stories that reach and connect the viewer to the human presence of people in the past. Handwriting and images peek through layers of color.

Hugo Pérez’s Loteria card masks frame the back doorway. Tezcatlipoca (Moon God) rises from the left, and Huitzilopochtli (Sun God) sets on the right. During the pandemic, Pérez hosted a small mask-making workshop for his close friends as way of reclaiming the masks they were wearing every day to protect themselves. Prompted by this exhibition, Pérez created a set of masks using Loteria cards which reminded him of his childhood and cultural background. The masks, one depicting the Sun God and at other the Moon God represent duality–a concept Pérez continues to explore in his practice.

Opposite of Caldera’s quilts are Helen Sharpless’s sewn works on stretcher bars and Cynthia Giron’s works on panels. I met with Sharpless over coffee to learn about what led her to sewing and her choice to choose textiles over painting. I am always curious how women learn their crafts in today’s world (in contrast to mid-20th century). Was it passed on to them by their mother’s? How has it influenced their relationships? Does their craft play a role in their identity as daughter or mother?

Unlike me (who just recently built up her confidence to use the sewing machine), Sharpless has been sewing since she was a young girl. She sat nearby as her mother sewed drapes and clothing. Enthusiastic, Sharpless started sewing thereafter. At Rice University, she created a sewn installation that flowed outwards from a house structure.

During the pandemic, Sharpless cut, sewed, and experimented with joining fabrics to create abstract patterns with specific color palettes. At times, the works are large and droop slightly under the weight. In others, the fabric is taught and controlled. As the exhibition continues into the third room, the works become even more probing. In Altered Remnants, cloth pushes forward to create a shaggy appearance, while in New B and Silk Meditation, satiny fabric stretches across to create a mostly smooth surface.

To the right of Sharpless’s Flag Dude, Cynthia Giron’s four mixed media works vibrate outwards. Given more time to reflect and address her own person health, Giron explored nostalgia and kitsch. The first painting, A gathering, presents a dinner table–a place associated with sharing and physical connection. The thing with Space is playfully investigates physical presence and emotional space in the form of a galaxy. FEEL LIKE and La Rata follow these two works by addressing personal reflection and family memory.

In the final room, the visitor will find Amanda Power’s series of crocheted plastic bags, works that derive from the Houston freeze, and works by Sharpless and Lechin.

$2/hour is an ongoing series by Powers. Using the craft technique of crochet, Powers loops together dollar signs from plastic bags–producing at most two per hour. During the pandemic, Powers was particularly concerned with the systems of power present in today’s global society and the social and environmental impact of our everyday actions. Transforming “trash to treasure” the objects evoke a since of resistance and communal empowerment against corporate negligence, while simultaneously questioning the value of money, the impact of over-consumption, and the individual’s role within the economic systems of society.

Lost Time and Power Grids were made during the Houston Freeze (2021). Both works use electrical cords as material and subject matter. Tangled, woven, and twisted, cords are severed, stripped, and cut. Powers describes the works best: “Electrical cords serve as physical remnants of the virtual spaces that, for many of us, sourced our only means of connection and communication during the lockdown. Seen here in these two works—an iPhone charger, ethernet cable, headphones, an extension cable, and additional power cords—these objects are obsolete when electricity is no longer accessible. The cold, blue paintings archive electrical cords as something of the past, while the hand-woven, material objects carry our memories, mending broken structures and reimagining new forms”.

Standing on a podium across Sharpless and Powers’s works, Lechin’s ceramic The Skin We Wear slips and slurps. It is a beautiful, organic black ceramic piece dotted with white. A later addition to the exhibition, I love how the form stands as both shadow and beacon for the tangible and bodily–encouraging viewers to relate the odd and unknown experiences of the exhibition to their own bodies.

When you visit this exhibition, I hope you see and experience the play, solace, and comfort as I did with these artists and these works. Each object is unique, vibrant and wonderfully human.

I am incredibly grateful for these artists and the generosity they shared in the form of their work. Please continue to make, share, and celebrate what makes us human.